Flood concerns linger like unsettled river silt

- Tal Galton

- Jul 19, 2025

- 8 min read

Unsurprisingly, the trauma of Helene still has people on edge here in the valley. Strong storms, or talk of hurricane season, stir emotional reactions. It’s hard to think clearly and logically when our mind’s-eyes are still trauma-fogged and our actual eyeballs see the lingering effects around us. Like a stormcloud always on the horizon, I’ve sensed a miasma of concern about the river. Call it a vibe. I get asked about the state of the river every day – is it safe? Is it healthy? Another example of concern about the river recently came to the forefront of the community: do the changes wrought by Helene lead to a greater risk of flash flooding?

A post on our local listserve was made by someone who had a recent harrowing experience of getting stranded on a rock in the middle of the river during a sudden and dramatic rise in the water level. She reached out to the county for more information on flash floods, and received this response: Flash Floods will be more prevalent until the mountains revegetate. Yancey County lost 62,000 acres of forest during Helene. I would also think the large tract of land along Highway 80 that was clear-cut, just below the parkway, didn't help the situation. Runoff from that property will hit the South Toe River quickly during periods of heavy rainfall.

It is understandable that folks are concerned about flooding. During this 10th month after our own devastating flood experience, we have collectively viewed scenes from Texas which look and feel uncannily familiar. Just days later came news from our own state, when TS Chantal surprised the Durham and Chapel Hill area with historic flooding. Meanwhile, we are in the midst of a mid-summer pattern of (occasionally heavy) afternoon thunderstorms. It is essential for people to be aware of the threat of floods in the South Toe watershed. Yet, it is important that we think carefully, and keep our heads level when we consider the dynamics of flooding in our own valley. We can blame Helene for the heartaches of displaced people and the destruction of cherished institutions and infrastructure, but we can’t blame Helene for our local hydrology. These mountains and their forests make incredibly beautiful, and occasionally dangerous waterways. Our rivers and their floods are a feature, not a bug.

Our community is nestled in a beautifully forested mountain valley, but it is rugged terrain and contains inherent risks. Recall what Margaret Morley observed over 100 years ago: “the valleys that nearly surround the Black Mountains are deep and narrow, and the streams rushing through them are very swift, clear, and, from the rapidity with which they rise during a storm, dangerous, the Estatoe, or Toe River, as it is commonly called, and its branches being among the most dangerous of the mountain streams.” As I like to say, every South Toe flood is a kind of flash flood (some flashier than others) since we are a headwaters river. Our watershed is relatively small, so heavy rainfall in the watershed, especially in the higher elevations (where the heaviest precipitation most frequently occurs) can swell our creeks and river very rapidly.

Tempting as it might be to think that Helene’s havoc has contributed to subsequent flash flood events, it is unlikely that the storm has increased the magnitude or frequency of flooding. Forest disturbance on a landscape-wide scale (blowdowns, landslides, etc) in the South Toe Valley, was relatively modest due to Helene (a very small fraction of our 28,000 acre watershed – see the image at right).

I plan to dig deeper into the data that went into the 62,000 acre figure for the county – most of that disturbance was in the northern half of the county, and the forest service’s definition of "lost" forest is used loosely and exaggerated. Likewise, the clearcut that is cited – it represents less than 1% of the watershed. As much as I'd love to blame flash floods on a clearcut – and that particular 200+ acre swath most certainly has a direct effect on that particular branch of Still Fork Crk – it is just a drop in the bucket of the entire South Toe watershed, and can’t possibly have a noticeable effect on the rate of water entering the river.

“Flash floods," like the one that stranded the concerned citizen on a rock, are not major river floods that leave the banks – those require a longer duration and generally larger storm – instead they are a sudden rise in the flow of the river that can be dangerous if you are in the water or near the water’s edge. The one on June 26 was an increase in volume from 65 cubic feet/second to 939 cfs in 15 minutes (between 5:15 and 5:30) – an impressive 14X increase in water volume! It was caused by a downpour near Mt. Mitchell during which it rained 2.4" in 45 minutes (according to the rain gauges on Mitchell and on neighboring Clingman's Peak). The river's rise was especially surprising to us in the valley since we only received .16" rain in Celo. But the river always rises rapidly when it rains heavily over the headwaters.

The scouring of many of the tributaries and the riverbanks does mean the water moves faster once it enters the creeks, but that would be pretty hard to measure, and I think is still a relatively small influence on the rate of river rise. The speed at which the river rises primarily has to do with how fast and how much rain falls from the sky. Thankfully much of the woody debris is still in place along most miles of stream to help slow the flow!

The most significant recent analogous event that I am aware of occurred on Aug 2 of last year (nearly two months prior to Helene) when the river rose from 91 cfs to 2400 cfs in 15 minutes (a 26X increase – or nearly double the increase of June 26, 2025). The sudden rise was similarly surprising since it had only rained .5" in Celo. Yet, it rained 4.73" on Clingman's Peak that evening, including 3" in 45 minutes! An interesting fact that I've learned from studying these two events, is that it takes about 2-3 hours for rain in the high elevations of the headwaters to reach Celo’s USGS streamgage.

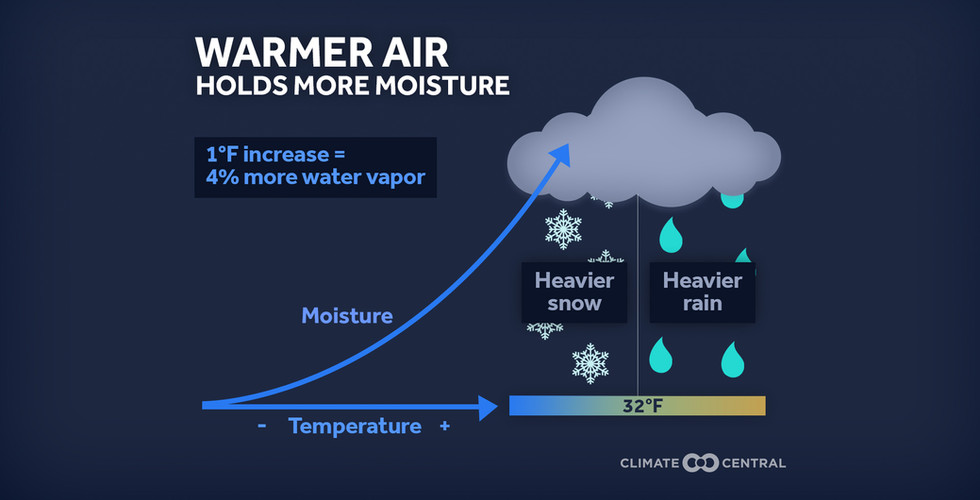

Sudden rises like this don't happen frequently, and I want to learn how to retrieve the data from the USGS streamgage that would tell us how frequently they occur on the South Toe (I’ve submitted a query to USGS to see if there is a way to search for, say, 10x rises in cfs over 15 minutes). The gage has been operating long enough that we might be able to tell if they are happening more now due to climate change (although this would still be a small sample size). In any case, we can probably expect more of them due to climate change. It is safe to assume that climate change is a much more significant factor than any forest damage caused by Helene when it comes to increased risk of flashier floods. If a very significant percentage of our watershed had been affected by Helene, or by fire, or by timber harvest, then it could have had an effect on flooding – but that was fortunately not the case in this instance. (Both logging and fire probably were factors in the Great Flood of 1916 when large swaths of the mountaintops had recently been cleared and burned.) What’s happening now is simple physics: the climate is warmer, and warmer air holds more moisture. Studies show that extreme rainfall events have already increased significantly, and that more increases are expected as the climate continues to warm. (Good luck chasing down the original data in the Fifth National Climate Assessment (2023). I clicked the link (https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/) but the current administration had taken down the website two weeks prior.) The bottom line is that extreme precipitation events (the rainiest 1% of days) have already increased nearly 40% in our region over the past 60 years, and we can expect another 30-40% increase as the world approaches 2 degrees C of warming (likely in the next 20-30 years).

Helene wreaked havoc on our human community, particularly on our psyches – and most especially on our sense of security. But we can’t continue blaming everything on Helene. Is the river healthy? Is it safe? We are incredibly privileged to live along a headwaters river. There are not many roads and homes and businesses upriver; it’s mostly still intact forest. As someone who enjoys the river on a daily basis, I can assure you that, aside from the places that people have destroyed habitat to rebuild infrastructure, the river is every bit as alive and healthy as it was before Helene. (More on this in a future post/article.) The river has changed, more in some places than others, and I am keen to learn from the remaining state and federal biologists who study the river what those changes are. The river is “safe,” too, as long as you pay close attention to the weather upstream.

Please don’t fear the river. Don’t fear it, but do respect it. I can say with geological certainty that the river will flood many more times again, sometimes as powerfully as Helene, usually less so, and perhaps occasionally even more so. We won’t live to see all of them, but floods will happen and will continue to erode our infrastructure until either we build it out of harm’s way or it has all dissolved into the river.

For more details on the dynamics of South Toe flooding, you can see this this blogpost from last October. The excerpt below describes the Aug 2 event.

When I posted here about the new signs, I cited a TVA study from 1960 calculating potential for severe Appalachian flooding. A flash flood can occur on a small watershed like our own little stream, Hannah Branch (~100 acres), or one of the creeks descending from the Blacks, like Locust or Shuford or White Oak (~1,000 acres each), due to an intense, stalled thunderstorm. A flash flood like this happened on August 2, when a severe thunderstorm erupted over the headwaters of the South Toe. My NWS rain gauge in Celo, at the very northern edge of the storm, registered a mere ½” of precipitation. But over the high southern peaks of the Blacks, from Potato Knob to Mount Mitchell, a downburst dumped 3” of rain in a 45-minute period (recorded on the NADP rain gauge that I help monitor on Clingman’s Peak). Fourteen miles downstream, precisely two hours after the deluge, the South Toe River surged from a bucolic 91 cubic feet/second to 2400 cfs in just 15 minutes. An Inn guest lost her wallet and sunglasses to the rising river as she rushed from the river up to the road. Such storms are possible in any of our smaller watersheds. The smaller the watershed, the more it is affected by an intense local storm.* The entire South Toe above the USGS gage is a medium-sized watershed (~30,000 acres), and it is unlikely that such a thunderstorm would be large enough to cause major flooding (over 12’ or 20,000 cfs) on the river. For major floods, we are dependent on a larger scale event, like a tropical storm.

Comments